Isabella reporting,

French women have always had a reputation for being fashionable, but Élisabeth de Caraman-Chimay, the Countess Greffulhe (1860-1952) made fashion into an opulent gesture of self-expression. While she was known as a patroness of artists, writers, and musicians and as a hostess whose

salons attracted the most brilliant members of European society, it is her sense of style that makes her so memorable today.

There are two reasons for this. First, she was immortalized as the fictionalized Oriane, Duchesse de Guermantes, in the famous novel

À la recherche du temps perdu by Marcel Proust. Second, her family preserved much of her famous wardrobe. The highlights of this collection are currently on display in the exhibition

Proust's Muse: The Countess Greffulhe at the

Museum at FIT in New York City through January 7, 2017. (Many of the pieces appeared first in an earlier exhibition organized by the Palais Galleria, Musée de la Ville de Paris, the permanent repository of the Countess's wardrobe.)

It's an amazing show. The earliest pieces date from 1887, when the Countess was a teen-aged newlywed. Already her taste - and her daring - are on display. There's a sleeveless, black lace bodice that would have been worn over a colored gown, not-so-subtle transparency that must have been shocking at the time.

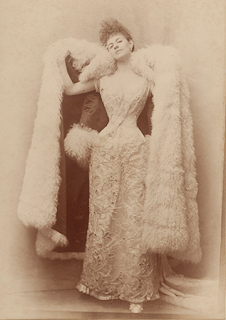

By the later 1890s, the Countess was not only commissioning clothing from premier couturiers like the House of Worth, but collaborating with them, pushing the designers to create the dramatic clothing she craved. She loved to be the center of attention wherever she went, and journalists devoted countless words to describing what she wore to the opera or theatre. She posed for photographers like Paul Nadar, and polished her "image" before that very-modern sense of the word existed.

One of her most famous dresses by Worth,

above left, was known as the "lily dress" for its bold black-and-white embroidered design. The photograph,

above right, shows the Countess wearing the dress, with her pose carefully staged with the mirror to display both the dress, and her own beauty.

To me perhaps the most extraordinary thing about the exhibition is that it includes clothes worn by the Countess throughout her long life, from the heavily corseted dresses of the

Belle Epoque to the narrower silhouette of the early 1910s,

lower left, to straight, beaded shifts of the 1920s,

lower right, to the beautifully cut and sinuous dresses and suits of the 1930s. Certain elements of her taste (for example, she frequently wore the color green, flattering to her auburn hair, and she loved exotic Byzantine prints and motifs) remain, weaving in and out of the changing fashions. Yet always her clothes remained constant to who she was, and how she wished to be seen - and remembered.

Unfortunately the Musée de la Ville de Paris prohibited visitor photography. You can see more of the Countess's dresses

here, on the the exhibition's blog, and on the museum's Flickr account

here.

Many thanks to Nicole Bloomfield, Costume & Textile Conservator, and Ariele Elia, Assistant Curator of Costume & Textile, Museum at FIT, for their help with this post.

Upper left: Evening gown, known as "La Robe aux Lis" (the lily dress) c1896, by House of Worth. Photograph by L. Degraces et Ph.Joffre/Galliera/roger-Viollet.

Upper right: The Countess Greffulhe by Paul Nadar, c1896.

Lower left: Evening dress, c1913, by Pierre Bulloz. Photograph ©Zach Hilty/BFA.com

Lower right: Evening dress, c1925, by Jenny. Photograph ©Zach Hilty/BFA.com.

Bottom left: The Countess Greffulhe in a Ballgown by Otto Wegener, c1887.

All images from Palais Galliera, Musee de la mode de la Ville de Paris.

Impending deadlines (which you’ve heard about more than once here) oblige us to start our holiday break a little earlier than usual. But we promise to be back in 2017 with more Nerdy History stuff. If you get too lonely for old things, in the meantime, please do search our archives. You might be surprised. We are, sometimes, when we look there—and realize we’ve accumulated seven years of material!

Impending deadlines (which you’ve heard about more than once here) oblige us to start our holiday break a little earlier than usual. But we promise to be back in 2017 with more Nerdy History stuff. If you get too lonely for old things, in the meantime, please do search our archives. You might be surprised. We are, sometimes, when we look there—and realize we’ve accumulated seven years of material!

One of us --

One of us --